288. WHELAN, Patrick. |

|||

| "I was to fly out and intercept Whelan in the desert, or beat him to his find, and ring his show with leases". | |||

|

Errol Coote, Hell's Airport. 258.

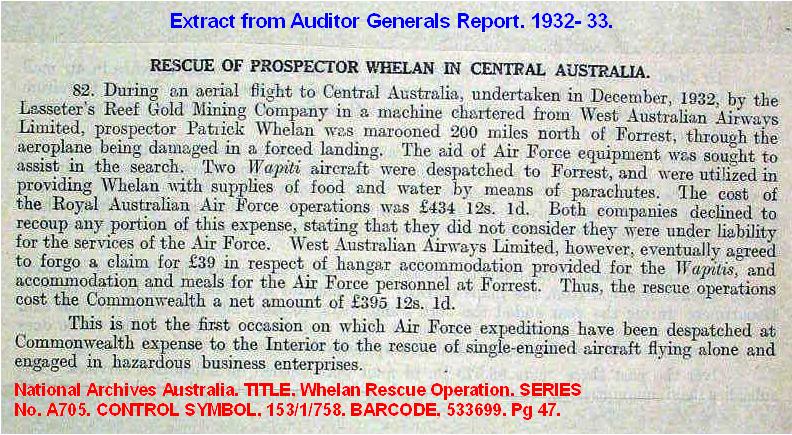

Paddy Whelan earns his place in Lasseter lore for several reasons, he instigated the first post Lasseter, lost gold reef scam, and caused Coote, the Baileys and H. W. B. Talbot some angst and further expeditions chasing Eldorado. He may have inadvertently put one of the paragons of Australian aviation out of business and certainly changed Aviation laws. Ion Idriess used Whelan's discovery to good effect in Lasseter's Last Ride, and by chance Michael Terry was on the scene. But a word of caution regarding Paddy or Patrick Whelan, apparently there were two of them knocking about the West Australian goldfields at the time, and both were known to be the West's answer to Bob Buck. Where either Paddy came from or went to is another story, but our Paddy of Whelan's Reef notoriety became famous for a misadventure and not for any gold he found. In the last page of later editions of Lasseter's Last Ride, Idriess writes that Whelan reported to the Mines Department on the 28th of July 1932, that he had made two rich gold discoveries somewhere 400 miles east of Laverton, in the vicinity of the Livesey Range or thereabouts, and note the qualifications, Whelan Country like Lasseter Country has ephemeral yet expanding borders, to the satisfaction of Idriess and Coote and many others it was found the borders overlapped, "This brings the discovery into 'Lasseter's country,' with interesting possibilities", Whelan and others lost no time in realising those possibilities, within the week the Livesey Range Gold syndicate was raised and plans announced to despatch an expedition to the area the following week. The syndicate had the wit and resources to appoint H. W. B. Talbot leader of the expedition. Press reports of Talbot's progress spurred Coote and the West Centralian Gold Exploration Co. to action, Coote gives the impression that the Company was preparing another search for Lasseter's Reef, in an unstated locality, when Whelan's announcement caused a hurried change of plans. The Company now decided to set up a base in the Warburton Ranges and at least be second on the field. Coote and his mate Stewart were in Melbourne, ready to fly to Kalgoorlie with Keith Farmer, when news arrived that the Talbot expedition had been forced back to Laverton due to lack of water. The West Centralian Co. immediately offered the use of their aero plane to help Whelan relocate his reef. Whelan and his backers, a Doctor Gorman and his father, would consider the offer without commitment, nothing had been heard from the Gormans by the first of November when The West Centralian Expedition left Kalgoorlie for Laverton. In fact Whelan had gone to ground for the time being. Coote and his mates were in Laverton, finalising plans for the Warburtons, when another explorer/prospector by the name of H. B. Lugg returned to civilisation, he had recently checked Whelan's find on the ground and in detail, "He was emphatic that there was nothing at the Livesey Range looking anything like a reef", undaunted the West Centralian Co. started operations from the Warburton Ranges on the 25th of November, under the keen eye of Michael Terry who made some trenchant observations about the Company and Coote in particular, and added that Whelan's find was a lot of nonsense. Yet Idriess in his authoritive bestseller was certain, "that Lasseter's country is proved beyond all doubt to be auriferous", based on press reports and unseen gold specimens. Meantime it had come to light that Whelan admitted to finding pegs for five to six claims covering his discovery, it was naturally assumed the pegs were Lasseter's and Whelan had rediscovered his reef. This announcement was opportune publicity for Ernest Bailey and C.A.G.E. who promptly and loudly threatened to sue Whelan and his backers if they tried to claim Lasseter's Reef, the Baileys and many shareholders in C.A.G.E. thinking that any gold reef found in Lasseter Country was theirs by association with the fellow who had given his life to find their fortune. Baileys threats were empty, his Company broke and discredited and out of business by the end of the year. In the Warburton Ranges Coote and Farmer flew far and wide under difficult circumstances, they first checked the Livesey Range and sighted the cairn built by Lugg to prove he had been there, then surveyed to the north and north west as far as Lake Christopher. Coote saw promising country everywhere, but the sandhills and time precluded investigation from the ground. Coote's expedition returned to Laverton empty handed and no one the wiser to Whelan's whereabouts. Coote and Farmer had just returned to Melbourne when Whelan resurfaced in a dramatic fashion, The plane in which he had been travelling with two others had disappeared on a flight to his reef, several days later the plane reappeared minus Whelan, he had been marooned on a salt lake several hundred miles north of Forrest in Western Australia and in dire circumstances pending rescue. Coote offered his services in the search for the plane and later the rescue of Whelan, he was not acknowledged, the players in part two of the Whelan Reef saga had larger agendas, quite beyond the capabilities of Coote. It all began on the 21st of December 1932 when the Lasseter's Reef Gold Mining Company hired a dilapidated D.H. 50 aircraft from Norman Brearley's West Australian Airways, it was a very secret deal to an unknown location, but obviously somewhere near the Livesey Range. The plane left Forrest the following day with three men aboard, the pilot was Harry Baker, N. S. Stuckey a mining expert and the prospector Paddy Whelan, the object of the flight was to land Whelan and Stuckey as close as possible to the reef so that Stuckey could carry out a detailed investigation. On the way the plane made a forced landing on a salt lake and overturned, resulting in serious damage to the plane and injuries to Whelan. The plane was overdue that night. From his limited and ramshackle resources, Brearley initiated an unsuccessful search next day, did nothing the following day and the day after announced to the press first that further searches would be made and Government help had been requested, he then contacted the Government, it was 11.20 p.m. Boxing Day 1932. If Brearley had hoped to catch the Bureaucrats and Government sleeping off Christmas then he was rudely awakened, Civil Aviation and the Department of Defence and a couple of powerful Senators were waiting for him with the law and regulations handy and a fat file on the recalcitrant Major Norman Brearley's past misdemeanours. Brearley was immediately asked to give an account of rescue efforts so far, and had he considered the absurdity of sending two Airforce machines with limited range and a crew of five, several hundred miles to the interior when West Australian Airways had two, soon to be three planes on hand. Brearley had no answers and did little for the next three days. On the 29th Civil Aviation learnt by inference that the missing plane had returned to Forrest the previous day, minus Whelan, because of weight restraints on the jury rigged plane he had been left behind. The search for a missing aircraft had now become a rescue operation for a stranded prospector. Brearley made a couple of desultory efforts over the next two days to drop water and food to Whelan and on the 30th attempted to embarrass the Government into taking over operations by announcing to the press that only the Air Force had the necessary equipment that would save Whelan's life whose situation was becoming critical. Brearley was a day late with his crude attempt at blackmail, Senator Mclachlan, Vice President of the Executive Council, had authorised two Airforce Wapiti planes to the rescue the previous day. Flying Officers Wright and Miles were given concise instructions, fly to Forrest, sort the mess out, rescue Whelan and put on a good show. They arrived at Forrest shortly after 2.00 p.m. on the 30th and found a rabble, true to his brief Flying Officer Wright took charge and there's a distinct inference in his report that some muscle was required. Brearley and Gorman Senior deserted the field. The Royal Australian Air Force got on with the job and by 10 o'clock on the last day of the year successfully dropped supplies for four days to Whelan. This gave Wright and his men time to maintain their planes, and repair Bakers wreck of a D.H. 50, in places it had been braced with mulga sticks and was probably unsafe before the Whelan stunt. Fuel supplies were organised around a likely train strike and a couple of radio stations set up. And it was made very clear to West Australian Airways that it was their rescue, the Air Force could keep Whelan supplied indefinitely. Baker thought he might be ready on Wednesday the 4th and It may have occurred to Brearley that his airfield, one of his aircraft and his publicity had been neatly taken over. He had remained silent since his ignominious departure from the scene. Bakers attempt to rescue Whelan on 4/1/33 was cancelled when a leaking oil pipe was discovered in his plane, the Wapitis already warmed up went ahead and dropped supplies to Whelan and a message to be prepared for rescue the following day. Meanwhile Sergeant Cameron from the Air Force took over repairs to Bakers plane and had it test flown that afternoon. Shortly after 5.00 a.m the following day the three planes left for the dry salt lake, now known as Whelan's Lake, 230 miles north of Forrest. Baker landed successfully and had Whelan aboard and safely away by 8 o'clock and at Forrest two and a half hours later, Whelan's condition was fairly good considering his privations, limping from a hip injury, nursing a broken finger and somewhat thinner, he was perky enough to be interviewed by the press and had the grace to thank the Air Force for saving his life. Flying Officer Wright, his colleague F/O Miles, Sergeants Cameron and Campbell and L.A.C. Thomson got on with maintaining their aircraft, they left Forrest on the 6th and arrived at Laverton, their base two days later. Miles had the satisfaction of including in his report, "Both Aircraft and engines completed the entire operation without a single replacement". In due course accounts for the Whelan Rescue Operation came home to roost, starting with Wright's report to the Air Board, it was damning, just one paragraph destroyed Brearley, "At this stage no further consideration was given to secondary means of rescue, and on the evening of 31/12/32 the Gold Company's representatives, Mr. T. Gorman and Dr. E. Craig, left Forrest for Perth; Major Brearley and Mr. N. Stuckey left the following morning. their attitude appeared to be that now the Air Force had arrived their own responsibility in the rescue of Whelan was finished. Before their departure it was necessary to confiscate from Mr. T. Gorman tinned foods brought to Forrest for the purpose of supplying Mr. Whelan; these supplies he intended taking back to Perth. These particulars are included in this report to show how attempts were made by the Gold Company, and also W. A. Airways, to shirk the responsibility of rescuing Whelan". The Secretary of the Air Board, aware of the bigger picture, added his comments, "the general attitude of Brearley and the Gold Prospecting Company representatives at the conference held at Forrest after Flying Officer Wright's arrival there is a most disquieting feature, whilst the action of the Gold Prospecting Company representatives in attempting to remove to Perth by train the foodstuffs collected for Whelan appears most reprehensible". Whelan, the Gormans and the dozen or so prospectors and speculators that chased his reef faded away, they were of no importance to the Government. They were after Brearley and were determined to use him as an example in a crusade to clean up Australia's airways. In Brearley's case it was done in a very subtle fashion, starting with leaked press reports that West Australian Airways could expect a bill from between £400 to a Thousand pounds for the Air Forces expenses. This had the desired result and Brearley replied to the Air Board that if the Commonwealth was prepared to drop the charges for the rescue of Whelan he would rescind the £39 he charged the Air Force for accommodation, meals and hanger storage, and foolishly added, "We have to advise you that we consider we are not under any liability to your Department for the services of the Air Force in connection with the Whelan expedition". The Air Board now had an admission in writing and proceeded to put Brearley out of business by the simple expedient of rewriting the heavily subsidised mail contracts for Western Australia in such a way that Brearley would not be able to compete. In 1934, to the surprise of many, he lost all mail contracts except the unsubsidised and unprofitable Perth Adelaide route, 18 months later he was forced to sell his aviation business to the competition, Australian National Airways Pty Ltd. It's not known if the formidable Mr. M. L. Shepherd, Secretary of the Department of Defence, had placed himself on duty over the Christmas New Year holidays or if he had been tipped off that something was afoot, he was ready and waiting for Brearley. Within the hour he had contacted Senator Pearce, the Minister for Defence, who happened to be holidaying in West Australia at the time and had already received a telegram from the lawyer representing The Lasseter Reef Gold Mining Co. and by some means Shepherd was aware of this. The Vice President of the Executive Council, Civil Aviation, The Air Board and the Air Force and all were of the one mind, it was a publicity stunt, more so considering the time of year, and it was an attempt to embarrass the Government. And with a nice sense of anticipation, Shepherd had a pair of Wapitis and a pair of DeHavilland Moths and their crews placed on standby. The immediate response to his telegrams should have alerted Brearley that the authorities were wide awake, one sharp reply from Shepherd at 5.30 in the morning told Brearley to use some initiative and improvise ways of delivering supplies to Whelan. Shepherds foresight in having two sets of planes on standby was well demonstrated when he deduced on the 29th that the problem was now one of dropping supplies to a lone man at a known location, for this task the Wapitis were ideal, rather than the slower but more economical Moths, better suited to searching for a missing plane in an unknown location. Shepherd despatched the Wapitis a matter of hours later. Brearley was utterly embarrassed when the Air Force arrived at Forrest the following afternoon, just that morning he had bellowed to all who would listen that the Air Force and the Government were endangering Whelans life through inaction. It not often you see a fellow hang himself with telegrams, perhaps Brearley thought Public Servants file and forget them, his messages and Shepherds replies went to the Solicitor General, who decided after some consideration that it was probably not worth the expense of recovering costs from Brearley, any legal action would probably send his rickety airline broke and he was quite capable of creating sympathetic publicity. It was worth three or four hundred pounds to the Government to be given the excuse to clean up Australian aviation, within months several laws were passed governing single engine aircraft, remote areas flying, maintenance of aircraft and keeping log books, aerial cowboys were no longer welcome in Australian skies. Flying Officers Wright and Miles, Sergeants Cameron and Campbell and L.A.C. Thomson received due accolades from those who mattered in the aviation business, Senior Air Force Officers were well pleased with their men and aircraft, in fact Wright was given carte blanche to liaise with the press, such was the impression he and his mates and their planes had made, more than one ordinarily cynical scribe noted that the Air Force achieved in a matter of hours what the other fellow failed to do in over a week. In it's final report, the Air Board included a paragraph with some emphasis, "Flying Officer Wright and the personnel under his command deserve much commendation for the efficient manner in which the Air Force part of the operations was performed, but reflects little credit on Major Brearley and his organisation generally".

© R. Ross. 1999-2006 20100322 |

|||

| Errol Coote, Hell's Airport. 257-280. Ion Idriess, Lasseter's Last Ride. Endpaper. | |||

|