| 3. AFGHANS. |

| "an afghan camel driver who was packing cinnamon bark picked me up". |

| BAILEY 1 |

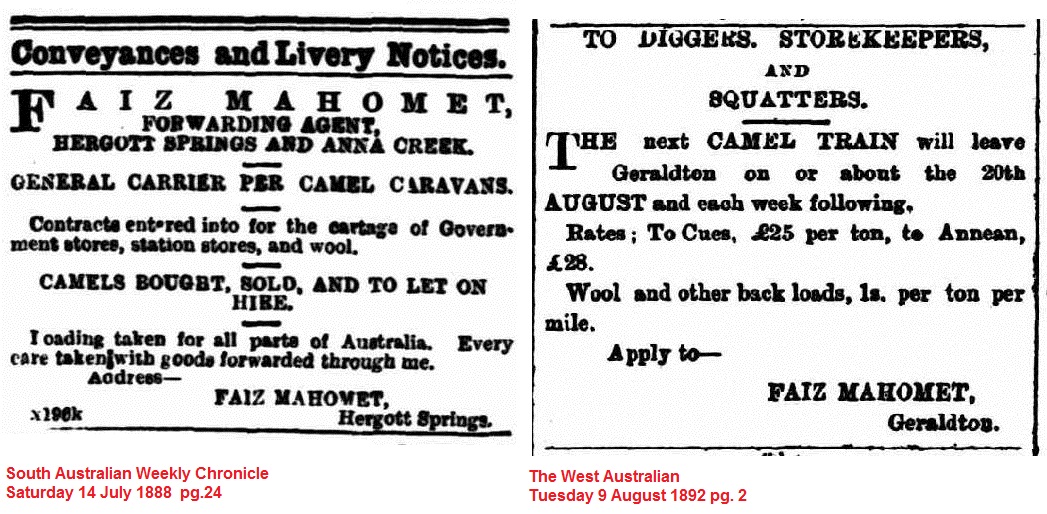

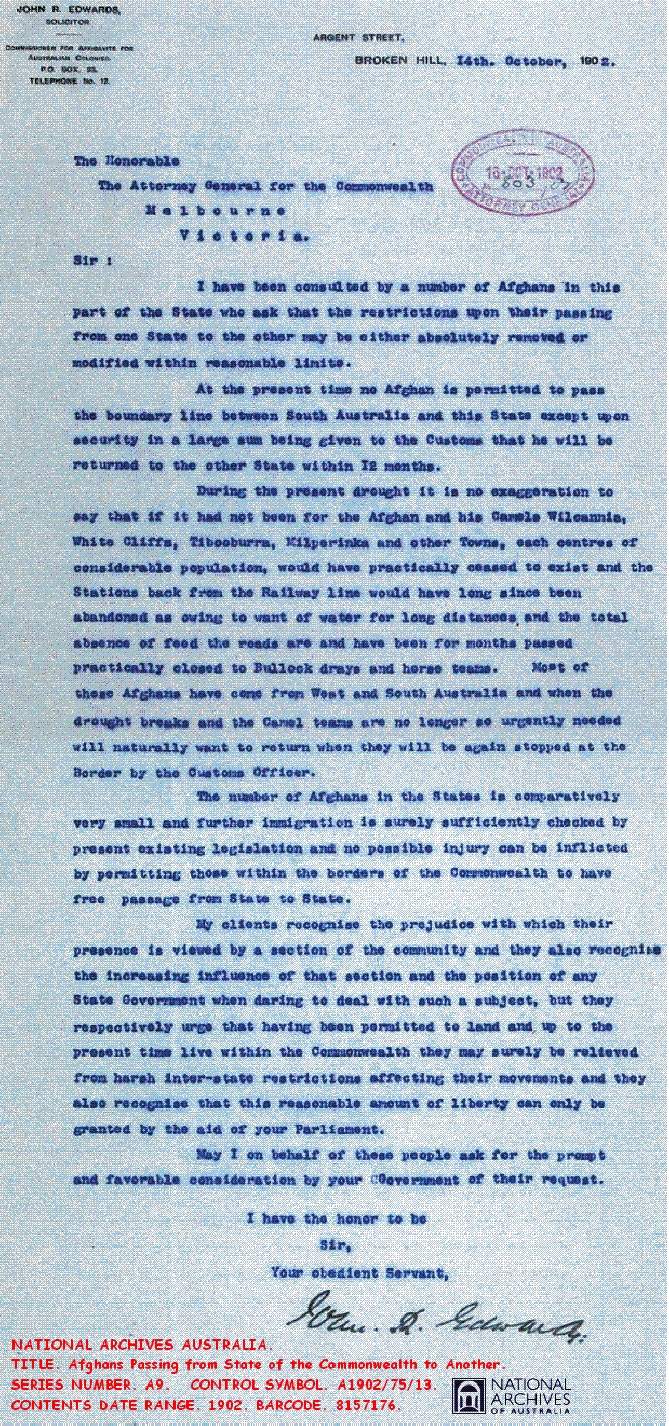

| Blakeley and Coote make only passing reference to Australia's Afghan pioneers although the Asian Camelmen enter the story at it's very beginnings. It was an Afghan sandalwood gather who found the perishing Lasseter in 1897 and took him to Harding's camp on the West Australian Stock Route. And like the rest of us, the men of the C.A.G.E. expeditions used the term in a generic sense when discussing Australia's first cameleers, but these hardy men would probably claim a tribal loyalty before nationality and consider themselves as Pashtuns or Baluchs, perhaps Punjabis or from Kashmir. But in the main men from eastern Iran, southern Afghanistan and Pakistan. Probably only Blakiston-Houston would appreciate the ethnic subtleties of being Afghan. Cigler in his book 'The AFGHANS in Australia' includes the Turkish Empire, the Middle East and even Egypt as recruiting grounds for cameleers to the Australian colonies, but wherever their origins these Muslim men are collectively and respectfully known as Afghans, in the context of this work and like Madigans spinifex, there the matter rests. The heyday of the Afghans and camel transport was the sixty or so years prior to 1930, and as the most reliable transport in an arid and drought prone land they soon had an elusive but continental profile. They were always few in number, certainly less than 5000 travelled to Australia as camel handlers and transport managers or merchants. They came alone, some worked out their contracts and returned home to wives and family, most stayed and prospered but few married and then usually to Aboriginal women, occasionally a wealthy Afghan would return from his homeland with a bride and very few white women married into Afghan society. Coote was critical of the romantic image of Marree and it's Afghans and one suspects he is alluding to Ernestine Hill, he disparages the "white women who have allied themselves with the Afghans", noting these women were usually "ostracised by decent society" long before secluding themselves in the hovels of Ghantown. Coote must have found these liaisons particularly disturbing, "a stark human tragedy".

From the European view the Afghans specialty and function was cheap but reliable transport to the remote and difficult parts of Australia, although respected and admired the Afghans had a social status between the Aboriginal and European Australians and Coote had his first experience of Australian apartheid or caste, when due to poor planning, he landed the Golden Quest in Marree's ghantown on 21/7/30, it took a firm warning and a stern glare from the towns assistant postmaster, "we draw the colour line very sharply here", before the dismissive Coote relocated the plane to the towns race track. On take off the crowd of curious Afghans were smothered, "with a cloud of red dust". An unnamed and possibly unemployed Afghan saved the day in Alice Springs in early October, 1930, when he supplied a piece of close grained oregon timber to replace the damaged engine bearers in the Golden Quest II. By 1930 men and machines like Freddy Colson and Sunrise were successfully establishing the next phase of inland transport, effectively making the Afghan and his camels redundant. But adaptive as ever many Afghans turned their camels loose and ironically worked on the railway line affectionately named in their honour. In Dream Millions Blakeley only mentions Afghans in the context of the contradiction in Lasseter's story about sometimes being rescued by an Afghan and sometimes a dogger. Surprisingly, Idriess passes up the opportunity in Lasseter's Last Ride to elaborate on the crucial role Australia's first camel men played in opening up the outback. Unlike Coote, he would have found plenty of romance in the story.

© R.Ross. 1999-2006 |

|

Bailey John. The History of Lasseter' Reef.1. Coote

E H. Hell's Airport. 63,64,180.

|

|

|

è |